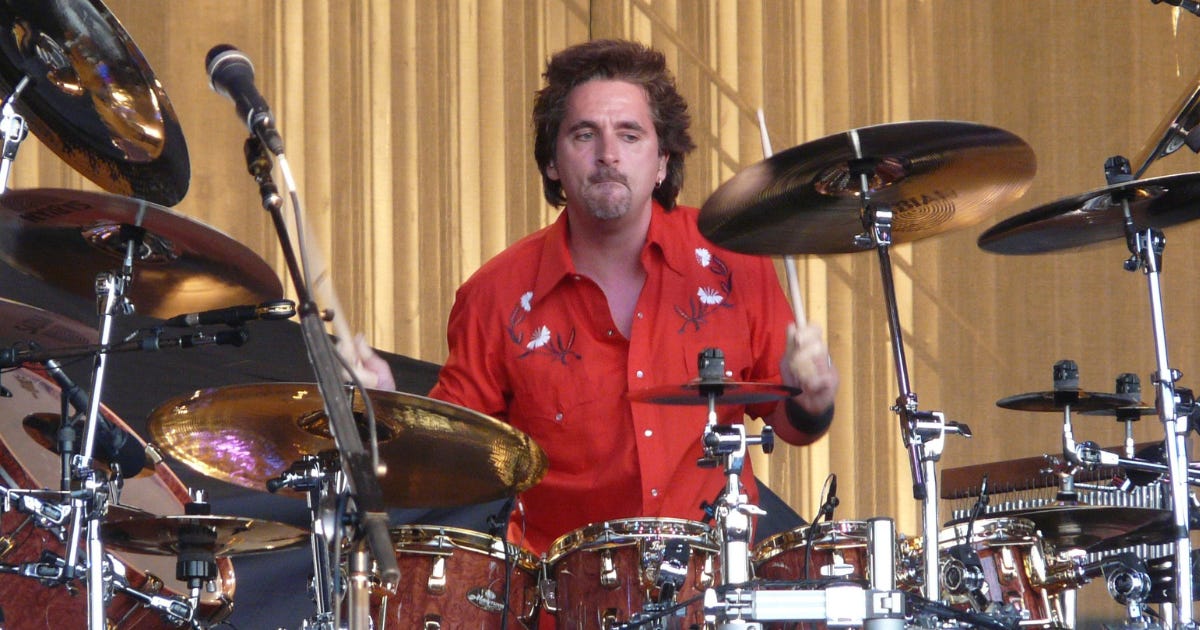

Director’s Note: “Todd Sucherman has been in my life longer than he probably realizes — not as a person at first, but as a pulse. As Power in Adventures of Power, he didn’t just play the part… he was the part: pure momentum, pure myth, the kind of performer who makes rhythm look like a superpower. Years later, getting to sit with Todd in conversation felt like stepping back into that same current — only this time, we weren’t talking about the spectacle of drumming, but the soul of it.

In this session, we go far beyond technique. We talk about the unseen work: the discipline of practice, the humility of the studio, the difference between chops and feel, and why music education isn’t optional — it’s a lifeline. Todd moves effortlessly from hilarious tour-life truth to deeply tender reflections on his father’s legacy, Brian Wilson’s otherworldly musical mind, and the rare warmth and integrity of Neil Peart’s orbit. He’s a monster player, yes — but what struck me most is his humanity: the way he treats rhythm like a moral craft, and groove like something you earn through attention.

This conversation reminded me that “power” isn’t volume. It’s presence. And Todd has it in every beat.”

The Power of Feel

Todd Sucherman is a virtuoso by any technical measure, but this conversation lives in the spaces between the notes. We talk about the long road of becoming — from air drumming on beds and pillows to holding down one of the most demanding seats in rock history. Todd breaks down the discipline of practice, the humility required to serve a song, and why “feel” isn’t something you can fake or fast-track.

Lineage, Legacy, and the Work

We explore the musical lineage that shaped him — a big-band drummer father, a house full of records, and a life steeped in rhythm long before the spotlight arrived. Todd reflects on his time with Brian Wilson, the quiet genius of hearing everything, and the profound generosity and integrity of Neil Peart’s world. Along the way, we dig into music education, creative responsibility, and the idea that rhythm isn’t just a skill — it’s a lifelong practice, earned through attention, patience, and care.

Watch video version here:

RAW TRANSCRIPT (Pardon the old-school glitches):

Ari Gold: Ladies and gentlemen, uh, who are here early, just so you know, we have a little bit—California has a little bit of the power outage situation that Texas had recently—and so our live stream on multiple channels is going to be postponed for a week. But those of us on Instagram were able to do this on our phones, so we thought we would say hi. Well, without power, um, yeah, that was the story of Texas a little over a week ago. We were okay here, but, uh, I felt like the sword of Damocles was over our heads—at any moment it could be lights out. Yeah, but it looks like you got power there.

Todd Sucherman:

Oh, we have power here, and because I play the character of Power in Adventures of Power, I always have power.

Ari Gold:

You’re never without. Never, never without. Um, so, uh, well, we’ll talk for five minutes because we’re here, right? I’m here. I got a bottle of water. You know what else we’re gonna do? We’re gonna have a party now. We’re gonna have a mini party. I have a costume—a piece of the costume from Adventures of Power. I have my Adventures of Power headband somewhere here. I—I’m already, those of you who don’t know, I’m, uh, on the Modern Drummer Instagram, um, but, um, normally—and higher back—um, I am in the Guinness World Records for air drumming, and I made the movie Adventures of Power, which Neil Peart was in. And, um, when we released the film, I also, um, punked Todd by going to a drum—I think it was a NAMM performance or something—and I went on stage and performed as Power air drumming. Can you guess what year that was?

Todd Sucherman:

2009.

Ari Gold:

2006.

Todd Sucherman:

No, pretty sure—I’m like 99 sure—there’s 2006. It’s possible because I was playing that character for a while before I even had made the movie. So that was the Hollywood drum show—the Hollywood vintage drum show. It was, uh, and yet because I had moved from LA to Austin in, uh, December of 2005. So it was still kind of weird, like, hey, I don’t live here anymore, you know, uh, at that time for me. And then some weird guy in the orange jumpsuit is air drumming on stage when you’re supposed to be—you did a Blue Collar Man, I think it was, right?

Ari Gold:

I did. Yes, I did Blue Collar Man because, you know, my character in the movie works in a copper mine. It seemed appropriate. Um, so, um, but yeah, I, uh, you know, maybe we can do the one question. Yeah, In the Air Tonight. Yes, people have seen the movie. So, um, the question that I was asking before we got on the phone—now we will do the one question, then we’ll come back in one week to do, like, a more in-depth chat that also is on YouTube and all the other places. Uh, tech problems for those who are just showing up. Perhaps you could tell these lovely people about, um, your experience with Spinal Tap because we, as you said, we share a colleague, and Michael McKean, who’s in Adventures of Power and is in Spinal Tap. So what was your Spinal Tap experience?

Todd Sucherman:

Well, I mean, for me, those guys are obviously—they’re a firing squad of comedy, yet they don’t laugh a lot. Like, they make each other—they say the funniest things and, you know, that Christopher Guest will go, you know, like—that’s him laughing—and sort of like that. But they’re all—they all want to play. They all can play, and they all want to be great. Um, and they were all just just lovely, lovely people. Yeah, the first time I worked with them was just over 20 years ago now, but, um, just wonderful people. They really—they actually care. They want to play and sing as well as—as they can. Um, and it’s funny—I hadn’t had any communication with Michael since around 2009, the last time I played with him. But I thought that he was so amazing in Better Call Saul. It was about maybe three, three years ago—three, four years ago. Uh, I thought, you know what? He was unbelievable. I couldn’t believe he wasn’t showered with Golden Globes and Emmys and stuff. I thought his performance was as good as anything anyone’s ever done on the screen. And I wrote him an email, and I went and played the show. It came back, and he sent me a lovely email back like that. So yeah, yeah—lovely guy.

Ari Gold:

Yeah, he’s a—he, um— I teased him occasionally on Twitter. That’s where our relationship is right now. Really real quick—there was something someone posted like, who’s the most handsome man who’s ever been on screen? And I posted one of my photos of him from Adventures of Power, and he wrote back and said, “Good boy,” because I play—I play his son, so it seemed appropriate. Can I geek out on one drum thing real quick? You mentioned In the Air Tonight. I have something very special here. Um, although I am a Pearl drum endorser, uh, I do have this—what I call the cantaloupe monstrosity—back there. Those are 1978 Premiers, which that is the exact same era drums that Phil Collins recorded In the Air Tonight. A lot of people think of—because he’s been Gretsch since ’83—he was Premier 1975 through 1982. So all those records, uh, you know, Lamb Lies Down to Broadway through Abacab—those were, uh, when he was playing for Peter Gabriel, and Peter Gabriel 3, which is kind of where I think the sound that he used on In the Air Tonight was developed by playing on, uh, Peter Gabriel’s record. When they were like, let’s do it. Let’s try our whole record with no cymbals, no hi-hat, no crash, no—no. Jerry Marotta played most of that record. I think Phil played two songs on that. I think he played, um, No Self Control and, uh, Intruder. And I believe they—they stumbled upon that—the backwards or the gated reverb thing—by mistake. Hugh Padgham was a producer, and he was just kind of hitting buttons, and all of a sudden they were getting sounds, and they thought, what’s that? So happy accident with Phil playing—or with Jerry Marotta playing—it depends on who you ask. Yeah. By the way, Tony—Tony just texted, uh, from Modern Drummer—just texted me. It was like maybe you guys just keep going. Should we just roll it? And then we’ll—I’m happy to talk. I’m like I said, I got a bottle of water and a bottle of water. That’s rock and roll lifestyle, man. But the bar is in the house. Like, I keep this, uh—so you’re, um—you live in Texas. You have, like, a—do you have horses? What’s a drummer’s life when he Texas?

Todd Sucherman:

I don’t have a cowboy hat. I don’t have, uh, horses. Um, I have a cat, um, and a daughter, and that’s—that’s enough for now. Um, but yeah, I moved—my wife and I moved to Austin, um, 15 years ago seeking—seeking a better life until weeks ago, and then it was like, maybe not.

Ari Gold:

Yeah, yeah. Until—

Todd Sucherman:

Until three weeks ago. Um, until they decided that there’s no power in the state of Texas. You know, it doesn’t matter that, you know, it’s 114 degrees here for 90 days in a row, and everyone’s cranking their air conditions—air conditioners—there’s plenty of power then. But, uh, dip the temperature to nine and it seems to make the power go like that. Who knows?

Ari Gold:

Yeah, well everything froze—the pipes froze and the gas lines apparently.

Todd Sucherman:

Yeah, I mean, it’s basically—basically take Miami, cover it with hockey arena ice, then dump snow on it for about five days and make it nine degrees for about 10 days and see how that works.

Ari Gold:

Yeah. Sexy stuff. Good times. Yeah. Um, so you—so you’re Texas now. You were raised in Chicago, right?

Todd Sucherman:

Correct.

Ari Gold:

And your father was like a big band drummer, is that right?

Todd Sucherman:

Yeah. I’m like, Mike—yeah—I’m sorry. Did he play like Buddy Rich style? My dad was more—he was more of a groover. Like, if you’re hip to like Dave Tough—Davey Tough—he was like a quarter-note pulse swing guy. He wasn’t like a technician, uh, like Buddy or a showman like—like Krupa. Uh, he was—he was kind of a pocket player. He had the sweetest buzz roll, press roll I’ve ever heard anybody do. Um, but yeah, he put himself through medical school playing drums. Um, and boy, I think he started college in like ’38 or ’39. So my dad was 50 when I was born. Uh, so yeah, he—he put himself through med school playing drums, and then he sort of had a dual life where he had a practice in the day and for like close to 19 years he was one of the house drummers at the Chez Paree in Chicago, which was like the Cotton Club. And that’s where all the big—you know, like Sammy Davis Jr. or Liberace or Joey Lewis or Sophie Tucker and all these like old-time Senior Wences—you know—all sorts of crazy stuff went down there. And he was one of the the rotating guys, uh, in the house band there for nearly 20 years. And, you know, he passed away when I was 22, and one of the questions I wish I could ask him is: How did you do that and survive on so little sleep for so long?

Ari Gold:

Yeah. What do you think, carrot juice?

Todd Sucherman:

Probably. I mean, there—there wasn’t—uh—[Laughter]—it wasn’t the ’80s, if you know what I mean. Uh, it was the—the ’50s. There’s sort of a different—uh—different things going on back then, right? Um, so, uh, yeah, I also—I also—I know eventually we could talk about sticks or no sticks. No, someone asked me what kind of air drumsticks I used. There’s also the sticks with the River Sticks band that you’re in, which we could talk about. But I also want to know about you playing with Brian Wilson.

Ari Gold:

Okay. What do you want to know? Well, I mean, he is—you know—he seems to have descended from upon—from upon high—onto the planet to write songs. But I would imagine that playing with him, working with him, you know, you’re dealing with a guy who’s got his—his ups and downs. And I don’t know what you feel comfortable saying, but what was it like?

Todd Sucherman:

No, I mean, the incredible thing about Brian is, you know, once you try to—you know—initially I was very intimidated because here is a individual who is also known for, uh, you know, peculiar behavior or being eccentric or whatnot. But he changed the face of 20th century music and—and sort of almost single-handedly was the architect of the quintessential California dream. So, uh, that is a pretty heavy thing. But you just realize he’s just kind of a—he’s just a guy. He’s like a Saint Bernard. He wants to clown around and have some fun if he’s feeling—yeah, there you go.

Ari Gold:

I started surfing. Why you guys started surfing, you know, uh—uh—guy planning. Sorry, I just had to pull up the surfboard because—no, but the—the funny thing about Brian is he—he really does hear everything. And, you know, I’ve just seen him like—you know—the band’s rehearsing and, “Hey Brian, what’s the trouble part?” “The first note of, uh, California Girls—C flat”—like that, you know. And it’s a weird note if you ever listen to the beginning. There’s a really weird low trumpet note that doesn’t sound like it belongs in the chord, but it’s one of those things that makes that what it is. And when you hear a band that doesn’t quite get all the chords, you hear something and it—it’s not right—kind of makes your teeth hurt a little bit. He has notes and things in there that are extraordinarily complex that very few people can figure out the right voicings for stuff. Um, but he hears everything. I once saw him write an original piece and he had the whole band around and he doled out parts four bars at a time starting from the low vocals all the way up to the high vocals. And it started out like, what? It’s a weird Jackson Pollock painting or something. And then all of a sudden he starts adding the high notes and there’s the sun poking out from the clouds. It’s wow. Absolutely extraordinary. Wow. So, um, and you—he ended up singing for—on a record for you and your wife. Did I—did I imagine that?

Todd Sucherman:

No. Um, when Taylor Mills—my wife—when I produced her first record, this was back in 2007, uh, we got Brian to kind of lend, uh, his harmonies in—in a vocal blend. And then, uh, and I got Tommy Shaw to help out on one song. So we each sort of got our big boss man to—to come in and give us a hand with the—the record, which was a thrill. I mean, to have Brian Wilson like just lay a little—little harmony onto your record is—that’s, um—well, dig dig this. Uh, you know—do you know, uh, Our Prayer from, uh, Smile? You know that piece of music?

Ari Gold:

I don’t. You know, I’ve—I’ve smiled. I never gave it up. Yeah. That Smile’s the whole universe. I know. Oh, and they’re people who like—I feel like they all become—they become psychotic when they go into the Smile and the Smiley Smile and—

Todd Sucherman:

Well, check—a good place just to start with that, actually, and work your way back is check out the DVD, uh, Brian Wilson, um, uh, California Dreamer. There’s a great documentary that’s lovingly done about Smile, and then the second disc is, uh, it was his current band at that time in 2004 playing Smile live. That’s a great place to start because you can see—you can see like there’s the triangle hit, there’s an oboe that comes in. It was really filmed well. Um, so that’s a good place to start because you can see—you can see like there’s the triangle hit, there’s an oboe that comes in. It was really filmed well. Um, so that’s a good place to start and—and go back. But—but we had Brian and his band, uh—it’s just an a cappella like a Bach chorale, uh, start, uh, our wedding. Uh, having Brian Wilson the band sing Our Prayer to begin, uh, our wedding ceremonies—friggin—you know—couldn’t imagine that when I was in high school.

Ari Gold:

Yeah. Pretty good. Pretty good. Not bad. Um, so, um, well how do you—so you said you—what do you play now? Are the drums—yeah, do you say Pearl? No, no—actual drums. Yes, I do know. I just—I just had my 21st anniversary of Pearl. I played DW air drums. You look—if you look Branches of Power there’s—there’s one scene with us with a stool, uh, that Power sits in. Normally he doesn’t use this stool, but it is a DW stool. Yeah. Not even acrylics, just—uh— but no, sorry, I talked over you. What did—what did you say?

Todd Sucherman:

No, no. I was—so much. I just had my—my 21st, uh, anniversary, uh, with Pearl drums.

Ari Gold:

Nice. So, and they’re about to have their 75th anniversary next month.

Ari Gold:

Oh okay. So there’s gonna be some online, uh, Pearl partying happening, uh, before too long. Good. And so who—who has been your biggest influence other than I suppose your father? Or—and I’d love to hear if you want to share anything about how—sure. I mean—well too—like how did your style form?

Todd Sucherman:

You know, my father was a big band jazz drummer. My mother was an actress who could also play a bit of piano and sing. Um, and I was the youngest of three. Uh, my older brother Paul gravitated to piano when he was a kid. Um, it was clear that I was going to be a drummer from the time I was a baby. And the middle brother, Joel, said, “Well, I’m going to play bass.” So I grew up playing with my brothers as a rhythm section under the tutelage of—of our dad. We also grew up in the era of rock, so there was that. Um, and the cool thing about being the baby in that situation is my brothers would meet older musicians and my dad knew so there’s always music playing in the house. You know, whether it was Led Zeppelin or Count Basie or Kiss or Aerosmith or Parliament Funkadelic or—what—Miles Davis. Like, it didn’t matter. There was always music playing. And then those guys would work with older musicians and befriend older musicians, so that opened up a whole other world of influences. My brother’s coming home with records and, you know, I mean, I have very vivid, vivid images of, you know, like my brother Joel coming home with Genesis Seconds Out. What’s that? You know, you see the album cover—let’s put it on, you know. Uh, it was a great way to grow up like that. And we had instruments and stereos in every room. So like I’d go to a friend’s house and I’d look around and go, “Where the hell are your instruments? Like, how can you live like this? You know, what’s the matter with you people?”

Ari Gold:

Yeah. I mean, the thing is—I mean, this is something that I really connected with Neil Peart about, um, was music education. And we, um—actually you donated a drum to our fundraiser. We—we reopened a music program in, uh, Jersey City at a public school and we raised enough money to completely—you know—the program had been terminated, um, and we were able to reopen it. And you know, the idea that there are kids growing up without playing music—to those who play music—does seem insane. It’s hard to fathom. And being the—the lucky recipient of a great, uh, junior high and high school music programs and—and band directors, uh—it’s—I can’t imagine not having that.

Todd Sucherman:

Yeah. It’s—it’s as important as everything. It’s math, it’s science. There’s—there’s been studies that—that kids can excel, you know, as their brains are formulating by—by playing music. And I—I don’t understand that. And it’s—I saw a great meme where, you know, if you want this and there’s a beautiful symphony hall of, you know, candelabras and you have to have this, and there’s a picture of a classroom with kids with violins. It’s as simple as that. If you want that down the road, well, yeah, it’s pretty simple when you talk it through like that.

Ari Gold:

Yeah. I always think about people who, you know—older generation people—who complain about hip-hop and rap music and—and then they don’t look at the fact that our country has stopped supporting music education for kids. So no one knows how to play instruments. So they do what they can—they make up words. Um, but I don’t think it’s a coincidence that hip-hop formed, um—or the—the early—the early guys doing hip-hop in the ’70s in New York—they formed like three years after the music programs were cut from the schools in New York City. Kids who were learning trumpet and you know all the drums—what—all these other instruments—they had no outlet for their musical kind of drive because they had no education, and then they started rapping, you know.

Todd Sucherman:

You know, I—I had, uh, I had a bit of a Grammy rant. I—I try to keep my socials, uh, positive and educational and whatnot, but when I saw the Grammys a year ago, I posted—in 1986—I said, “Hey, you remember that time when Buddy Rich played with Tony Williams and played with Stanley Clarke and Freddie Hubbard and, uh, like—yeah, I remember because that’s what they used to televise at the Grammys.” And there’s this whole performance of all these jazz greats. And where the Grammys have gone now—uh, although they’ve been great supporters of MusiCares—I don’t want to dump on them, but it’s a spectacle show now. It’s not an awards—when I was a kid I used to like to see, you know, the best recorded classical, you know, and there’s some guy from Austria coming down and accepting his award—he was the best engineer. Now all those are given—it’s earlier in the evening—and it’s—it’s—it’s—it may as well be Solid Gold or—you know—uh, it’s a big award show because let’s face it—you know—the Pepsi and whatnot—they—they’ll pay big money for that. But I said, “There’s not one thing I saw last night that would make a kid want to pick up a trumpet or a trombone or a violin or anything.” Oh, you might want to be a dancer or a celebrity—a star—but not a musician. And music’s biggest night—that—that—that really got to me. And my—my post was shared by like Stanley Clarke and, you know, all these people saw this post. And it made me feel good because those guys—they got the chance to be on TV, you know. I said that—that is—that is something that is denied to, uh, the musicians now and the viewers now. I—you know—I saw Al Jarreau singing Blue Rondo a la Turk with Art Pepper—who’s Art Pepper? Well I know who he is because I saw it. All these things—I—I got to see when music was—was—was televised. So I think that’s part of it. Part of it too—why is a kid going to pick up an oboe if he never gets to see one? Mm-hmm. Sorry, I didn’t mean to go dark.

Ari Gold:

No, no. I mean, it’s—it’s true and it’s a—I mean the whole culture has—I mean we could have, uh, we could have a big discussion about what’s happening in the culture. Let’s—but let’s, um, let’s pivot. Let’s pivot to sticks—not drumsticks, not my air drumsticks—but sticks with the “y” in the middle. Uh, how did you—you want to tell a little bit about how you ended up—

Todd Sucherman:

Sure. Um, well that—that came about from my good fortune of breaking in and breaking through the recording studio scene in Chicago in the early ’90s, and this would have been March of 1995. The guy who ran the cartage company that dealt with all the musicians—meaning he—he and his crew—if you had a session they were the ones that would come to your house, grab your gear, take it down to the studio, set it up, you go in, you play, sign a form, get paid, they tear it down, bring it back to your house. It’s awesome. So he had worked—Keith Marks, his name—he had worked with the band in the past. He’d worked with a couple of guys on their solo projects. And in ’95, A&M was going to release Stixx’s greatest hits—their first hit, Lady, was on Wooden Nickel Records—and apparently there was some issue about getting the sound rights recordings from the blah blah blah blah, so they decided, well, let’s re-record it. Uh, and at that time, uh, John Panozzo—Stixx’s original drummer—was in ill health and kind of couldn’t physically play the drums. So they called Keith and they said, “Who should we get to ghost drum, um, on the session?” And—and Keith said, “Oh, you got to call Todd.” And I also saw them in ’81 and ’83 and, you know, was in bands with my brothers playing, you know, a bunch of the songs. So being from Chicago—they were a Chicago band—they’re on the radio all the time—it definitely in my musical DNA as well as, you know, a million other bands and kinds of music and whatnot. So that—that was it. I just went in and, uh, recorded that track, and it was sort of—I was in and out of there 90 minutes. Nice to meet you guys and—and left. But they—they—but they thought—they phoned me back in February of ’96 to do another song, and this time was a definitely a much more get to know you. You know, they’re asking me questions, and I think they weren’t nice before, but I could definitely tell something was brewing, and they were sizing me up as a guy because there’s—when you’re on the road there’s 22 hours that you might be together—traveling or hotels or restaurants—where you’re not on stage. So they were—they were sizing me up as a—as a person to see like each other.

Ari Gold:

Yeah, yeah. Um, a fan is asking: Have you ever had a chance to collaborate with Thomas Lang?

Todd Sucherman:

Uh, no, but I’ve met Thomas a few times. Um, but, uh, but we’ve never—we’ve never done anything together.

Ari Gold:

Okay. Yeah. So yeah—inspirational drummers I kind of want to get back to because your technique is—I mean, I don’t know how many—I don’t—I don’t know who’s better than you on—on the planet. You’re there. There’s plenty, there’s plenty.

Todd Sucherman:

Okay. There’s plenty. There’s plenty. Okay. So who—who—yeah exactly. Now I provoked you. Who—who are your—who are your heroes?

Todd Sucherman:

You know, I literally—I have a list that I have, you know, like a cut and paste when someone says who your favorites are, and I just cut and paste like 150 names, and they go, because it’s true. But if I were to pick, um, like the holy trinity, uh, it’d be Tony Williams, Steve Smith, and Vinnie Colaiuta. But then I go, well how can I, you know, keep that and not add Steve Gadd or Peter Erskine or, uh, Simon Phillips—Dr. Gadd—you know what I mean? And each name there’s, you know, I can go down to Roy Haynes, Jack DeJohnette, or I can go, you know, Neil Bonham, uh, Keith Moon, you know. This—it starts to be like this musical tree of, of, you know, some English guys like Mark Rosicky, Mel Gaynor, um, Phil Gould, Gary Husband, you know, Phil Collins. I can go on and on and on. I’m sorry, what’d you say? Ginger?

Ari Gold:

I was never a Ginger guy. Too crazy. It just—it didn’t speak to me. That’s simple. He never really spoke to me either. Watching him sometimes, I’ll like watch some videos on YouTube, just like—I find like listening to crazy drumming before I go to bed is like the best head massage, you know? It like cleans out—you cleans out whatever it—whatever is in your day that you need to get rid of so you don’t have bad dreams. But so I’ll watch some Ginger Baker, and I feel a massage. But musically, I never got super turned on by him the way I did with other guys. But, you know, yeah, you know, it’s just one of those things like—and sometimes you just miss something, you know what I mean? Like, uh—and then when you go back it—it’s like, um, it’s a historical—a homework—it’s an archival thing that is—it becomes a history lesson as opposed to truly having it mean something and—and—and touch me. Um, so it’s—it’s hard sometimes doing that, uh, you know, some sort of Jurassic dig to find out something. Sometimes it can be fun. Sometimes you’ll be thrilling and—and it—and it does hit you. And then sometimes you go, it just doesn’t. It just doesn’t do it for me. It’s not my flavor. So yeah. Well, simple as that. Um, so, um, yeah, so what’s—what’s going on with Stix right now?

Todd Sucherman:

Well, uh, you know, nothing is insofar as us doing any shows, of course, obviously. But we did record what will eventually be the next Stix record. So I did that right here. Um, and with the technology today, my engineer, JR Taylor, was able to run my studio rig with a program called Audio Movers. They could listen to—and then Tommy Shaw and Vankovich, who’s producing the record, they could listen with the private invite link in full high-resolution audio in their studios. And then we got into a Zoom call. And if it was, “How about a different fill going into the second chorus?” “Okay, punch me in.” Boom. And we did 17 tracks in three days here, like that. And I was wildly prepared for it because I was supposed to record the record in April in Nashville in Tracks in three days.

Ari Gold:

You were really prepared. Yeah. Was I— I mean, I’d been prepared a couple months before and then COVID came and it was like, what the hell are we gonna do? Were you changing tunings and changing positions for—based on the song, or was everything kind of locked down in terms of your—your kit?

Todd Sucherman:

Everything was locked down. I would change snare drums for—that would be really the flavor change. Um, I may have changed hi-hats on one or two things, but I kind of wanted this where the mission—I had kind of switched a lot of cymbals, I switched snares, I used the same kit. I wanted to have it a little bit more a band thing. Like, like if you—if you called me to do your record, one of the questions I’d ask you would be: Do you want me to find different sounds for what I think is each song, or do you want like a uniform band sound? You know, if you listen to Synchronicity by The Police, like that’s the same snare drum all the way through. Yeah. That has a uniform thing. Um, you know, think how different Every Breath You Take would have been with a big deep snare drum, you know? But it could have worked. So I’m not good—so that—that’s where we’re at with—with the Stix thing. And it—it doesn’t make sense for this particular band to put up the record until we’re able to go out and play because we—we promote the records much better in a situation where we’re out playing them than just putting it out there. And you know, it’s not—let’s face it—it’s not 1981 where it’s just everyone goes—goes crazy. There has to be—people have to hear it and go, you know what? That Stix stuff’s freaking great. And then they buy the record. So during—during lockdown, have you been playing every day? I mean, do you do you feel—do you—do you actually practice? I mean, this is a good question for all the drummers out there. Like, does Todd practice? Does he still practice?

Todd Sucherman:

Yes. As a matter of fact, I’ve probably had more time to practice because I’ve been at home as opposed to being on the road. You know, there’s only so much you can get done on a hotel bed or in the practice pad or, you know, the little practice pad in the dressing room. And I’m not one that goes out for a sound check and blows on the drums because our crews have had a hard day. The last thing they—they need is just—you have some guy, you know, wanking on the drums. So for here it’s been great because I’ve had more time to do that. At the same time, I’ve been very, very fortunate that I’ve had a bunch of sessions and a bunch of records where I’ve had to prepare the music ahead of time. So it’s been artistically, um, a very fertile time for me to be able to roll up my sleeves and record a couple records that, you know, a couple progressive rock things are, you know, you know, seven, nine minute songs—things that I really want to compose and play the best that I can, as opposed to just improvising and going, “Huh, is that cool?” Uh, you know what I mean? So it’s been—it’s been a very fertile time in—in that regard. Do you think you’re—I mean, what’s—what’s the—what are you proudest of that you’ve created in the last year?

Todd Sucherman:

Ah boy. A bunch of things. I did my own record last year that came out in May. The new Stix record just is really excellent and has progressive rock leanings. Uh, I just finished, uh, this record—this guy—so I mean that term can mean different things to different people. Like, what—put it in the camp of with some other—other bands or—or records from which I would want the aggressive rock. I mean, I hear that term and obviously that to some people that means only stuff that was like in the mid ’70s that where there’s 17-minute songs. And other people are like, “Oh, Queen’s right,” because, you know, like, what does progressive mean to you?

Ari Gold:

Yeah. Well, I mean, to—to me, um, you know, like yes, Genesis, um, but like until 1978. Like, you know, what’s the cutoff? Yeah, I know that—that that’s—that’s a good one. You’re making me think, Ari. Um, I’m a film director. No. Yeah, I mean really. If—if you talk about songs that have some, uh, time signature changes, some different sections where all of a sudden something will come in, you know—something that’s not the three minutes and 25 second, you know, verse chorus—uh, verse chorus bridge guitar solo out, right? Uh, that type of thing. So, um, you know, yes, this is some really cool keyboard stuff. And Lawrence Gowan is a freaking, you know, monster player. He studied the classical at the Toronto Conservatory. So, I mean, his—his facility on the instrument is ridiculous. Um, so yeah, there’s some—there’s some really cool things on—on the record that it—it leans more in that direction than, you know, the Bon Jovi rock chorus like hit sounding thing, uh, straight out of the gates. So yeah, yeah. Okay. Um, so, uh, someone’s asking me what films have I directed unless they’re asking you. Maybe they’re asking—I think they’re asking me. Yeah. I made a movie called Branches of Power, uh, which is about air drummers. Um, it’s a comedy. Michael McKean from Spinal Tap plays my father in it—a union organizer—and someone who—who Todd has also worked with. Um, and some of you who’ve been here since the beginning have heard that. But, uh, and I made a movie called The Song of Sway Lake. And I have a TV show that I’m pitching right now. Big A—not independent thing. I’m moving out of this indie world into Hollywood and surfing in the meanwhile to keep myself from killing people. Um, uh, yeah. So that’s well—that’s enough about me. So, uh, you started drumming at like when you were like four, right?

Todd Sucherman:

I—I was two actually. But—but by the time I was four I was—I was—I was playing. Actually, I was playing this kit right—

Ari Gold:

You were doing timpani with this Chicago Symphony. Let’s just play this kit right—right here. Well, this one’s Slingerland with an 18-inch bass drum—that was my father’s last kit—my first. But I was playing timpani by the time I was four. And I did my first paying gig with my brothers when I was, uh, six. That’s—um, that—that does go part of the way to explaining your level of prowess. I mean, I talked to—I talked to Lars Ulrich who said he was air drumming for years before he got a drum set. And Neil Peart as well was playing pillows. He told me that he, uh, he was playing pillows for like a year before he got a drum set. Uh, he had to prove to his father that he was serious, so he played those pillows. Well, you—you know, Ari, that—that’s the plight of so many drummers. Uh, I—I have a show on Drumeo I do every—a streaming thing I do every Wednesday. And last show I was talking about how at some point we all fell in love with this. Whether you saw Ringo on the Ed Sullivan Show or you saw a Fourth of July parade or you saw, you know, your cousin had a drum kit in the basement—whatever it was—whatever—you came to this. You saw this and you—you thought, “That looks like fun. I want to do that.” And then the journey begins. Like, you got to convince your parents, or you got to get a paper route to pay for stuff. And then your dad might go, “Well, you get a practice pad for a year, and if you—” You know, everyone has their own journey to how they—they got to their—anything—drum set. Then the sound of those old practice—practice pads—they were horrible. At least now they have those like flatter rubber ones that are quieter. It’s amazing. A whole generation didn’t end up with carpal tunnel and tennis elbows. Oh, that’s—you know—that sound they were—they were just awful, awful sounding. But I—I gotta tell you, man, like there’s a thing about air drumming and I’m gonna—I’ll—I’ll tell you. It—you know, I was fortunate that I had drums, but points of the evening it was too late to play or something else was going on. Or maybe one of my brothers had a cold and he went to bed early, so I would play drums on my bed. That was one option. And then another thing was—you close your eyes—and I would learn kind of playing along with records. Or even—even into my 20s back when I would, you know—well, when you’re 21 and—and you might partake in some things that you do when you’re 21 and you’re up till 5 o’clock in the morning and you’re by yourself and you’re just playing music—I know what you mean. But you just go back and forth on the tape deck and just air drum that part. “What the hell is that?” It’s a tool to—to learn when you can’t sit at the drums. Yeah. It’s as simple as that. I mean, I—as—as the—the only person in the Guinness Book for air drumming—this is my claim to fame in life—I will say that air drumming, like you can’t—you can’t mess up. You can’t fake it. And so when I learned the air drum song, you know—and there’s also an athletic element of air drumming where you’re essentially have to—you have to have the strength to do each beat in double time because you—you can’t—there’s no—there’s no rebound. So you’re going down and then up. And so if I drum a hard song—you know—a hard song—I’m not a great drummer—but if I—I drum a hard song and I get through it, I’m fine. If I air drum that song and get through it, I gotta lie on my back for 10 minutes. I’m exhausted. So it’s—and I think it burns into your brain when you air drum or play pillow or whatever because you’re imagining that drum set around you and you don’t have it. And so, you know, yeah. And you’re—while you might experience a sensation of weightlessness, you do—you do have to—it’s a—it’s a there and back.

Todd Sucherman:

Um, though I don’t rely on rebound from the drums. I gauge the rebound because a snare drum is going to give me more love than a 18-inch floor tom. And you know, a 20-inch crash is going to feel different than a 10-inch, you know? I mean, each—each instrument on your drum set has a different feel and response. Which drum gives you the least love? Uh, the gong drum. The—the twenty is gonna—here, I’ll take you back to the gong drum because—that—that’s it. That’s a 20-inch head, you know? It’s not—it’s not tensioned and taut like—like—like a snare drum pillow. You can just lie down on it and—in it. Yes. You could—you could—you could take a nap. You could just lie down and really, you know. But wake me up in 20. Um, so yeah. It’s—you know, got a 22-inch crash over there. That—that—that—that’s going to feel different than a 17-inch crash. The—there’s the response. Um, but I—I—I know what you mean. It’s—it’s all you when you got nothing.

Ari Gold:

Yeah. I got some—a couple people have asked if you ever did anything with Jeff Porcaro.

Todd Sucherman:

I never met Jeff, no. Um, a lot of mutual friends, um, but I—I—I never got to see him play live. I never met him. Uh, I—I just read the Robin Flans book. Uh, finished that a couple months ago and—and went down a ridiculous Jeff listening rabbit hole. And you know what? What’s funny—and I don’t know if it’s you get to be at a certain age—but there are also certain things that I didn’t like when I was a kid that I hear now and I’m like, “My God, that’s great.” Yeah. So Toto was one of them.

Ari Gold:

Yes. No, I wasn’t going to go Toto. Uh, one thing in particular was When I Need You—Leo Sayer. That used to be an instant, “Turn that off, turn that off.” You know, like I wanted Led Zeppelin or The Who or whatever. Like, turn—you know, you know, I’m—I’m nine years old, whatever, and you’re getting picked up from Little League and that’s like, “Turn that off.” I just thought it was a sappy 6/8 romantic wussy ballad. And then there was talks about people talking about how great that song was. I’m like, “Geez, I didn’t know that was Jeff.” And then I went and listened. I wouldn’t listen to it. It was like the jaw just went like—like the feeling that’s just freaking stupid. Yeah. His feel is this, um, some kind of magic. Always.

Todd Sucherman:

Yeah. I, um—you know—you—you can—you could ask—you could go on a yacht rock playlist and he’s played on half of everything. But all those people on that—on, um, on Lowdown—I think it’s Lowdown—it’s a fun one to listen to in stereo and take off—take off one ear and the other because he has two hi-hat patterns going—one in each ear. He played twice in the studio. I mean, probably more than quite—he was—he was pissed about that.

Ari Gold:

Oh, really?

Todd Sucherman:

He—he didn’t want the—the—the 16th notes. He’d recorded it one way and the producer wanted it. And like he was like reluctantly did the—the double tracking on it if I remember that right from the Robin’s book. Like, from an arrangement point of view he didn’t like the fact that they were gonna actually run both of them at the same time because he—I think he felt that it wasn’t as hip as the track that he did and that they were trying to make it just that much more disco than what he did.

Ari Gold:

Yeah. I mean, but it worked. Yeah. You know, it’s—it hits. I mean, I—I—I love the feel of that even—even if it’s, you know, some kind of soup of multiple takes. Um, it’s—but he—he had—he had a magic thing where, you know, there are certain drummers when you know Gadd makes me feel that way—Steve Jordan—where they could be playing the simplest groove and I go, “How are you doing that? How are you making it feel like that?” And like, yes, I know. Yeah. As everyone’s got their own heartbeat and everyone’s got that. I think I—I can—I can intellectualize and understand it like that. But still, like okay, now sit down and make it feel like that. You’re like, “How are they doing that?” That’s—that’s the thing that I’m trying to really zero in now and not like, you know, chops or trying to play, you know, difficult polyrhythms that, you know, very few will understand or enjoy. Um, I—I want to be able to—to make something feel, uh, as great as I can make it feel. And—and that’s something that I—I always tried to do like growing up as a kid. But I was caught up in the—I loved chops. I loved playing, and almost to my detriment. I—I gained a lot of facility, a lot of understanding, um, to play a lot of stuff. And now it’s—it’s—I just—I just want to make it feel great.

Todd Sucherman:

Yeah. I love it when someone comes to me for a session, you know, and it’s a ballad or something with brushes. I’m like, “Oh, thank God.” Thank you. They always come to me with like, “Let’s get Todd on them.” Oh, I mean, I just—it’s my favorite thing in the world to do. Yeah. Quite honestly. Yeah.

Ari Gold:

So who—who would you love to have a collaboration with out there on planet Earth that you haven’t? Anybody that you haven’t yet, you know, is—yeah, because a person. There must be somebody out there you’re like, “I’d love to do a track with blah.” It’s like, “Oh sure.” You know, Peter Gabriel will, Sting, Paul McCartney, you know? I mean, you can—Jeff Beck—you can go down the line of all the greats. But, um, I’m—I’m often surprised by a random phone call from someone. Or, “Hey, are you available?” And it’s something I don’t know. I started to say I did this record two years ago for this guy in Germany. Uh, it’s called Finally George because he, um, he has been, uh, a music composer for jingles and film and, uh, corporate events and corporate films—stuff like that. But this is the first time that he’s been able to do his own music without someone standing over his shoulder telling him yes or no or what to do. And, you know, very often I’ll get sent stuff and I’ll—I’ll play something and my wife will kind of go, “You can’t put your name on that.” Or, in this case, “Who is this?” And just three great progressive rock songs. Like, if you—if you dig like the David Gilmour side of Pink Floyd or the—the mellower side of Porcupine Tree—little bits of Genesis—of Billy Joel and Bowie, um, with Parsons and—assistant Billy Joel together, right? Yeah. There are all these little bits. So I—I did this record and I treated it like it was my own record. And so I just finished his second one just last week, uh, and he’s become a friend in—in—in Germany. Uh, uh, uh, I’ve done both his records and it’s—it’s—it’s like with music that good all I can do is not screw it up, you know? So, uh, you know, I’d love to play with more people like that. So someone that I’ve never heard of that—that comes out of the blue and becomes part of my life—that’s—that’s the amazing thing about this. I could pontificate over like, “Gee, it’d be great to work with Sting,” but then there’s something like that comes and it—and it makes me almost weak on this is why I want to want to be a musician. You would sound great with Sting though. And they’re saying the same thing, by the way. Thank you. That would be fun. And Ringo’s All-Star Band. Have you met Ringo?

Todd Sucherman:

Uh, twice. Yes. Uh, yes twice. Um, sorry, what’s that German record called?

Ari Gold:

Uh, Finally George: Life Is a Killer. That’s the one that came out in 2018. And whatever his second one I just finished—that should hopefully be out sometime later in the year. But it’s—it’s—it’s on, you know—it’s on the Amazon, Spotify, whatever you however you listen to your music. Uh, it’s there. It’s really, really an amazing record. Okay. Okay. Um, what’s the hardest Stix song? That’s a question I’ve gotten several times. So I’m going to throw it at you. What—what song that makes you a little nervous when you’re about to play it live?

Todd Sucherman:

Well, I—I never get nervous, but I always hope that I have gas in the tank for Renegade at the end because that’s where we end the show with that. Um, Fooling Yourself is deceptively hard. It seems kind of like a happy song, but there’s a—there’s a lot—there’s a lot going on up here because it’s—it’s 12/8 to 4/4 to 7/4, um, and then kind of—that’s prog. But it—but it’s—it’s got—it’s got the Peter Gabriel Salisbury Hill 7/4 where you don’t realize it’s in 7/4 unless you go, “Hey, wait a second,” because it’s got a groove. Yeah, exactly. Um, so yeah, I—I—I’d say—I’d say those. Um, sometimes Miss America would—would kick my ass a little bit just because it’s like, you know—it’s like, you know—it’s like this—this big big bone bone head straight ahead rocker. And depending on where that is in the set or if it’s 100 degrees and 100 humidity outside when we’re doing the show, that can, uh, that can wreck me a little bit sometimes.

Ari Gold:

Hey, I—I want to—I want to ask you if I—if I could because I only got to meet Neil Peart once and I had a beautiful experience with him. And it’s—it’s very cool that that, um, you know, obviously it was—it was in the film, but you—you obviously connected with him enough to have a—a—a—a—a friendship. And, uh, you know, I’m curious of any—anything you’d like to share about your experience with him.

Todd Sucherman:

I mean, he—you know—he—he was, uh—look, I didn’t—I consider it more like a mentor that, you know, he was someone I always looked up to who would, um, you know, send me funny notes sometimes. We exchanged books. Um, you know, he was gonna maybe teach me to ride a motorcycle, which never happened. We—we had some plans—amazing plans—that he wanted me to air drum with the—the, um—what it’s called—the hockey—the Canada hockey theme or Canada Day—Hockey Night in Canada—fucking night. Yeah. So he has this big thing that he would do and—and he wanted me to air drum along with it. And, um, but you know, I think we connected—we—we first met on the set of Adventures of Power. I’d never spoken to him. I sent this letter to his management saying that I wanted him to be in this crazy independent movie about air drumming. And everyone said, “Oh, he’s a recluse.” You know, he—he just went through all this crazy stuff. He doesn’t do public stuff. He doesn’t appear on camera. And then word came through that he wanted to do it. And so I was totally flattered and—and intimidated. And, um, and then he actually couldn’t make it to set the day we shot his scene at the end of the movie when he’s at the—anyway, for anyone seen it, there’s a big competition. He shows up. So he wasn’t there when we shot the competition. So we—we built a special day where we like went to a studio and put a bunch of people to make the crowd so he could do his scene. Um, and I thought, “Oh this is so rinky-dink,” you know? It just like—it looks so silly, you know, because when you’re shooting a crowd scene in like a room and you’re faking it. Um, and the fact that it was so rinky-dink I think really charmed him. And so he immediately kind of warmed to the film and to us when he realized we were, you know, scrappy independent filmmakers. And he told me—we had a burrito back, you know, when we were waiting to shoot. And he said, “You know, this reminds me of, you know, when—when we were—when I was starting out as a musician.” And it’s so—it’s so great. He kept saying, “It’s, you know, it’s an honor to be working on something like this.” And then—and then when the movie, uh, you know, we finished the movie, went to Sundance and got kind of ignored slash attacked at Sundance. It was a kind of like really open-hearted comedy that at the time I think people didn’t want. They wanted something really cynical and mean. And so it was not well received actually. And he immediately contacted me and said, “Don’t believe anything anyone says about you—good or bad—uh, because if you believe the good ones you’re gonna believe the bad ones.” So just ignore it. And then he did these, you know, he did an interview with me at Drum Channel and then did this drum off where he played Tom Sawyer and I—I air drum right next to him while he’s playing it. And I mean, it’s like the life—lifelong dream of like millions of air drummers around the world. But, um, his generosity—I think he had this generosity mixed with obviously like a heavy brain. Like, he was super intellectual—a big reader, big thinker. Um, I actually challenged him a little bit about the—about the objectivism, um, you know, that it was so influential to his early lyrics. He said, “You know, what’s your feeling about,” you know, Ayn Rand now? And he kind of gave me a funny look like he—that he was over it. That he—I think he became a bit more open to spiritual ideas and open to certainly ideas about—uh, did I get caught off there for a second?

Ari Gold:

Yeah, you just froze for just a second.

Todd Sucherman:

Yeah. He kind of—he became more intrigued by stuff of the spirit and stuff of, you know, Mother Earth, which you can hear in some of the later Rush albums and the lyrics. Um, and so we connected on that. And, um, but you know, mainly I—I—it would—it was someone who made me feel—I think made everyone who met him feel, uh, welcome and protected and warm. Um, you know, for someone who is known as being a recluse or more distant—you know—you can never get to him—um, he was extremely warm. But he just—you know—he didn’t like dealing with like massive people coming at him at once. So like, you know, I—I got to get backstage passes to Rush shows and, you know, but he never showed up backstage, you know? He was—he was out. You know, he would, um, he would finish the show and—and go home. Boom. Yeah. He wanted to be with his, you know, his wife. And, um, so, uh, you know, this—I mean, I have his book, you know? He sent me his books whenever they came out. And it’s just relentless creativity. I don’t know. It’s—it’s very hard to have him gone from—from where I am. I know so many people that were in that circle or that orbit. Our guitar tech of 20 years, who died about six months before Neil did—Jimmy Johnson—was Neil’s boyhood friend and he was part of the deal when Neil got the Rush gig. Jimmy comes with. So Jimmy was with—with him all the way. Lawrence Gowan—when he was going in the ’80s—he was Ray Daniels was the manager. Um, uh, Libby Gray—our lighting designer—her husband’s Brent Carpenter has been doing monitors for Rush for the last 10 years. So through like Lawrence—like, you know—I know these people. And Howard Ungerleider—the lighting director—and everything I’ve ever heard about any of those guys is that they’re just exemplary human beings. It’s just it’s a wonderful organization of wonderful human beings. Uh, never heard one, “Hey, this one time.” Never heard one negative story or anything. Like, just exemplary human beings.

Ari Gold:

Yeah. Rush and them—they didn’t tolerate—they didn’t tolerate assholes, I don’t think. They wouldn’t have let anyone who was a douchebag into their world. And I think they had a sense for it too. And that’s where I was sort of flattered that they sort of the door opened for me to hang out a little bit, and—and it was—it was yeah. It was special. And—and yeah, you felt that from everyone. There there was a kind of like a sense of like everyone respected everyone else and, um, and was kind. It wasn’t like rock and roll BS ever, right? All right. Um, when I—my—my one meeting with him, uh, revolves around the Hockey Night theme. Uh, I’d flown to Los Angeles to record, uh, with Brian Wilson. And he was doing his, uh, uh, Gershwin record—both reimagined Gershwin. Every time you say that—every time you say, “Oh, and I went to record with Brian Wilson,” it’s—yeah, it is amazing. I’m not for free. Okay. Did I mention I was in Central Pay—no, no. Um, so I fly out there and I’m—and I’m staying at the—the Sportsman’s Lodge in—in Studio City, right? Uh, and I get an email from Jimmy Johnson—our guitar tech—and said, “Hey, look what Neil sent me.” And it’s a picture of the hockey drum set, right? With all the, you know, the—the white with the ice blue, uh, hardware and all the—every emblem of all the, uh, NHL teams on all the drums. So I’m like, well I was thinking it was cool, you know? Went to bed. Woke up. Went into the studio to—so actually this was the second day because my stuff was already set up. It was the second day. I walked in and I see Chris Danke from Sabian—the Sabian artist rep—in the—the foyer at the Ocean Way. I’m like, “Chris, what are you doing here?” He goes, “Todd, I saw Brian’s name on the door. I wondered if you were going to be here.” Like, “What are you doing here?” “Neil’s recording the hockey night theme and the next studio over.” He goes, “Now’s a good time to say hi.” I’m like, “Let me drop off my stuff,” and I’m starving. So I dropped off my stuff and I went and grabbed a bagel from the kitchenette, took a bite, and then all of a sudden Chris pulls me in. And in his studio there’s the kit, the freaking Stanley Cup trophy, an 18-piece big band, you know, all the techs, and a film crew filming this thing. And Chris introduces me and just, you know, warm handshake and a smile because we both know we have so many, uh, um, mutual people in our lives. And he was just warm, engaging, lovely. He was asking me all the questions. He wanted to know about the Brian Wilson record and what’s it like working with Brian and, you know, tell me some Brian stuff. Um, and, you know, I’m looking around and I basically see that there’s 27 people in this room all waiting for him to be done talking to me so they could get to work. But Neil seems to be quite happy to be chatting. But now I’m starting to feel a little bit like I should probably let you get back to work here. So Chris is all, “We got to get a picture.” So it snapped a couple pictures of—of Neil and I in the Stanley Cup, and I’m holding that friggin bagel with a big crescent bite out of it. Um, and that was my—my one meeting. I’m like, “Hey, uh, I’ll let you get to work,” and I—I got work to do too. So it was great. And I’d always hoped that there would be some other meeting with him, but it was not meant to be. But I’m very happy that I privileged and grateful and thankful that I had one and that it was so, uh, lovely. That it’s a warm fuzzy every time I think of it. Did you keep the bagel?

Todd Sucherman:

No, I ate the bagel. I was hungry.

Ari Gold:

I’m gonna say you could bronze—bronze the big—[Laughter]—bronze bagels. Um, so maybe we’ll—we’ll wrap up. I—I don’t, um—maybe I’ll look at whatever the next question is. We’ll do one question now. Everyone’s going to type it once, and—and someone’s going to feel cheated. But, um—oh, people just say thank you. Um, so bronze the bagel. Okay. I think maybe we’ll wrap up. So, um, anyone who wants to watch Adventures of Power, it is on Amazon Prime all the time. Um, and, uh, if you want to buy Adventures of Power on Vimeo, all of the money that we make on Vimeo goes to support MusiCares, which has a COVID—COVID special program to support musicians in need and for gigging musicians and support crews. It’s a really great charity. Um, so—or you can go to MusiCares and just donate. But if you watch Adventures of Power either on Amazon for free, you know, we get paid a couple pennies every time someone watches it, so we send it to MusiCares. Vimeo—we got a little bit more—we send it to Music—Arizona—Vimeo. You get all the bonuses including my interviews with Neil Peart and stuff like that. Um, and, um, yeah, Adventures of Power is—that’s the movie. Um, airdrummer.com has some video. Actually, if you go there—if you go to adventuresofpower.com/sticks you can see me punking Todd the day that I—um, that video is—is on your page on—on the airdrummer.com website. So apologies—2006. I can’t—2006—that’s crazy. I can—I can hardly remember 2006. I—but I can’t—I mean, I remember that day, but I—I wouldn’t have thought it was that long ago. But, you know, time—time flies. As—as the movie starts with the line I was thinking when you’re talking about every drummer has their own heartbeat, the first line of the movie is: “The first sound we hear is the beat of our mama’s heart.” And so maybe every drummer is different because in the womb every drummer has heard a different kind of heartbeat. So—and your mother was an actress—actor, actress—part-time singer and could play the piano. Okay. That was—that’s how my parents met. My father was playing a show and she was in it. Okay. So you heard—you heard the heartbeat of an artist when you were in the womb. And you were probably—you were probably air-drumming along.

Todd Sucherman:

Yeah. I mean it certainly didn’t seem to hurt because you were playing. Yeah. Sorry. Um, okay. So, uh, thank you so much, Todd. It’s a—it’s a real honor to—to hang out with you.

Ari Gold:

Thanks man. It was a pleasure. We’re able to do—we’re able to do this. Yeah. And thank you to Modern Drummer for, uh, hosting this. Uh, we were going to be on all the channels at once and we will restream this to all channels later. We, uh, had a power outage at our streamer’s place. But, um, thank you so much. And anyone who wants to watch Adventures of Power right now with me—with me online, um, uh, if you go to airdrummer.com and then click the—the, you know, the show link in the middle with where Todd’s name is, you’ll go to a watch party on Amazon. And I’ll click start at the same time in like five minutes. And then if anyone wants to say anything to me during—during the movie, you can say it there. But if you watch it another time, feel free to contact me at Ari Gold. That’s where I am on—on Instagram. And, uh, remember it all supports MusiCares. That’s my spiel—spiel. I said my spiel part. Todd, anything else you want to say about your life or advice?

Todd Sucherman:

Yeah. Like, stay—stay safe. Stay smart. Do the right things, everybody. And, um, and keep playing music. If—yeah, if we can all do that, we can—we can get back to, uh, the live music experience. Yeah.

Ari Gold:

Okay. Uh, thank you so much. I’m gonna remember—remember—remember when I click the button to stop to not to hit save so we can re broadcast this. We’ve got a lot of compliments on the interview, so I don’t want to lose it. I got to remember I’ve done this before. Right now I won’t say anything. I won’t distract you. It’s okay. I’m gonna say goodbye. I’m gonna press the button. I’m gonna hit save. Hit save. Okay, good luck. Thank you, Todd.

Todd Sucherman:

Thanks man. I know it’s too late for me to learn to play drums. I can still rock.

This interview originally appeared on Hotsticks.fm.

See more about Styx on the official site for Adventures of Power, the world’s greatest (and only) Air Drum Movie!

Enjoyed this session? Explore more from the Interviews Archive.